Learn how to choose the healthiest selections of meat and poultry and how to prepare them using low-fat methods. With these tips, you can reduce the fat even in higher-fat marbled cuts. Then you can have it both ways—taste and health.

CHOW Tips offers plenty of helpful info, like how to choose fresh meat, how to choose packaged chicken, how to grill, how to make the perfect hamburger, how to carve turkey, and more.

Choose from 38 quick and easy CHOW Tips that will help you cook like a gourmet, or even a chef.

Meat

- Menu

-

Meat is animal flesh that is used as food. Most often, this means the skeletal muscle and associated fat and other tissues, but it may also describe other edible tissues such as organs and offal.

In the Anglosphere, "meat" is generally used by the meat packing industry in a more restrictive sense—the flesh of mammalian species (pigs, cattle, goats, sheep, etc.) raised and prepared for human consumption, to the exclusion of fish, poultry, and other animals. Game or bushmeat is also generally distinguished from that produced by agriculture.

The consumption of meat has various traditions and rituals associated with it in different cultures such as kosher and halal and its production is generally regulated by state authorities as well.

Methods of Preparation

Meat is prepared in many ways, as steaks, in stews, fondue, or as dried meat like beef jerky. It may be ground then formed into patties (as hamburgers or croquettes) or sausages, or used in loose form (as in "sloppy joe" or Bolognese sauce). Some meat is cured, by smoking, pickling, preserving in salt or brine. Other kinds of meat are marinated and barbecued, or simply boiled, roasted, or fried. Meat is generally eaten cooked, but there are many traditional recipes that call for raw beef or veal (tartare). Meat is often spiced or seasoned, as in most sausages. Meat dishes are usually described by their source (animal and part of body) and method of preparation.

Meat is a typical base for making sandwiches. Popular varieties of sandwich meat include ham, pork, salami and other sausages, and beef, such as steak, roast beef, corned beef, pepperoni, and pastrami. Meat can also be molded or pressed (common for products that include offal, such as haggis and scrapple) and canned.

Red vs. White Meat

Meat can be broadly classified as "red" or "white" depending on the concentration of myoglobin in muscle fibre. When myoglobin is exposed to oxygen, reddish oxymyoglobin develops, making myoglobin-rich meat appear red. The redness of meat depends on species, animal age, and fibre type: Red meat contains more narrow muscle fibres that tend to operate over long periods without rest, while white meat contains more broad fibres that tend to work in short fast bursts.

The meat of adult mammals such as cows, sheep, goats, and horses is generally considered red, while domestic chicken and turkey breast meat is generally considered white.

Nutritional Content

All muscle tissue is very high in protein, containing all of the essential amino acids, and in most cases is a good source of zinc, vitamin B12, selenium, phosphorus, niacin, vitamin B6, choline, riboflavin and iron. Several forms of meat are high in vitamin K2, which is only otherwise known to be found in fermented foods. Muscle tissue is very low in carbohydrates and does not contain dietary fiber.

The fat content of meat can vary widely depending on the species and breed of animal, the way in which the animal was raised, including what it was fed, the anatomical part of the body, and the methods of butchering and cooking. Wild animals such as deer are typically leaner than farm animals, leading those concerned about fat content to choose game such as venison. Decades of breeding meat animals for fatness is being reversed by consumer demand for meat with less fat.

Red meat, such as beef, pork, and lamb, contains many essential nutrients necessary for healthy growth and development in children. Nutrients in red meat include iron, zinc, vitamin B12 and protein. Most meats contain a full complement of the amino acids required for the human diet. Fruits and vegetables, by contrast, are usually lacking several essential amino acids contained in meat. It is for this reason that people who abstain from eating all meat need to plan their diet carefully to include sources of all the necessary amino acids.

| Source | calories | protein | carbs | fat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fish | 110–140 | 20–25 g | 0 g | 1–5 g |

| chicken breast | 160 | 28 g | 0 g | 7 g |

| lamb | 250 | 30 g | 0 g | 14 g |

| steak (beef top round) | 210 | 36 g | 0 g | 7 g |

| steak (beef T-bone) | 450 | 25 g | 0 g | 35 g |

The above table compares the nutritional content of several types of meat. While each kind of meat has about the same content of protein and carbohydrates, there is a very wide range of fat content. It is the additional fat that contributes most to the calorie content of meat, and to concerns about dietary health.

Human Health Concerns:

-

Consumption of large quantities of meat, like overconsumption of any caloric food, has certain adverse effects which can include: obesity, heart disease, and constipation. In recent years, health concerns have been raised about the consumption of meat increasing the risk of cancer. In particular, red meat and processed meat were found to be associated with higher risk of cancers of the lung, esophagus, liver, and colon, among others, although also a reduced risk for some minor type of cancers. Another study found an increase risk of pancreatic cancer for red meat and pork.

-

Animal fat, particularly from ruminants, tends to have a higher percentage of saturated fat vs. monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat when compared to vegetable fats, with the exception of some tropical plant fats; consumption of which has been correlated with various health problems. The saturated fat found in meat has been associated with significantly raised risks of colon cancer.

-

Nitrosamines, present in processed meats and in meats cooked at high temperatures such as as in frying, have been noted as being carcinogenic, being linked to colon cancer. Also, toxic compounds called PAHs (Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) present in processed meat and meat cooked at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing, are known to be carcinogenic

-

The spoilage of meat occurs, if untreated, in a matter of hours or days and results in the meat becoming unappetizing, poisonous or infectious. Spoilage is caused by the practically unavoidable infection and subsequent decomposition of meat by bacteria and fungi, which are borne by the animal itself, by the people handling the meat, and by their implements; the latter two are the most common scenario.

The bacteria most commonly infecting meat while it is being processed, cut, packaged, transported, sold and handled include Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli, B. proteus, Staph. epidermidis and Staph. aureus, Clostridium welchii, B. cereus, and faecal streptococci. These bacteria are all commonly carried by humans; infectious bacteria from the soil include Clostridium botulinum. Among the molds/fungi commonly infecting meat are Penicillium, Mucor, Cladosporium, Alternaria, Sporotrichium and Thamnidium. As these microorganisms colonize a piece of meat, they begin to break it down, leaving behind toxins that can cause enteritis or food poisoning, potentially lethal in the rare case of botulism. The microorganisms do not survive a thorough cooking of the meat, but several of their toxins and microbial spores do. The microbes may also infect the person eating the meat, although the microflora of the human gut is normally an effective barrier against this.

-

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is an enterohemorrhagic strain of the bacterium Escherichia coli and a cause of foodborne illness. Infection often leads to hemorrhagic diarrhea, and occasionally to kidney failure, especially in young children and elderly persons. Transmission is via the fecal-oral route, and most illness has been associated with eating undercooked, contaminated ground beef, swimming in or drinking contaminated water, and eating contaminated vegetables. Emergence of this strain of E. coli is often attributed to the standard use of antibiotics in animal feed in order to increase their growth and to combat the array of diseases they contract by being raised in closed high stock density confinement. The 2011 E. coli O104:H4 outbreak in Europe is caused by the enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain O104:H4.

-

Although not a common cause of illness, Yersinia enterocolitica—which causes gastroenteritis and the disease yersiniosis in humans—is present in various foods, including cattle, deer, pigs, and poultry, but is most frequently caused by eating pork and can grow in refrigerated conditions. The bacteria can be killed by heat. Nearly all outbreaks in the US have been traced to pork.

-

The pig is the carrier of various helminths, such as roundworms, pinworms, hookworms, etc. One of the most dangerous and common is Taenia solium, a type of tapeworm. Tapeworms may transplant to the intestines of humans, as well, when they consume untreated or undercooked meat from pigs or other animals. If the infection is not treated, it can be fatal.

-

Since it is unknown whether chronic wasting disease, a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy among deer (similar to mad cow disease), can pass from deer to humans through the consumption of venison, there have been some fears of contamination of the food supply. Recently, several known cases of the disease have occurred in deer farms throughout the United States. However, farmers now have had tests developed especially for the particular species they raise to obtain better results than those used on cattle.

Back to Menu  |

Domestic Pigs

Pigs are known to be intelligent animals and can be trained similarly to dogs, though they may excel in different tasks. Pigs have been kept as pets, especially the pot bellied pig.

Pigs are known to be intelligent animals and can be trained similarly to dogs, though they may excel in different tasks. Pigs have been kept as pets, especially the pot bellied pig.

The domestic pig is mostly used for its meat, pork. The word pork denotes specifically the fresh meat of the pig that is left unsalted, but it is often mistakenly used as an all-inclusive term which includes cured, smoked, or processed meats (ham, bacon, prosciutto, etc.). It is one of the most-commonly consumed meats worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BC.

Cuts of Pork:

Pig carcasses are first split along the axis of symmetry into "halves", then the following basic basic sections from which other subdivisions are cut:

-

Head – used to make brawn, stocks and soups. Jowls (pigs' cheeks) are also considered to be a delicacy. After boiling, the ears can be fried or baked and eaten separately.

-

Blade Shoulder – contains the shoulder blade. It can be boned out and rolled up as a roasting joint, or cured as "collar bacon". Not to be confused with the rack of spare ribs from the front belly. Pork butt, despite its name, is from the upper part of the shoulder. Boston Butt, or Boston-Style Shoulder, cut comes from this area, and may contain the shoulder blade.

-

Arm Shoulder – can be cured on the bone to make a ham-like product, or used in sausages.

-

Loin – can be cured to give back bacon or Canadian-style bacon. The loin and belly can be cured together to give a side of bacon. The loin can also be divided up into roasts (blade loin roasts, centre loin roasts, and sirloin roasts come from the front, centre, or rear of the loin), back ribs (also called baby back ribs, or riblets), pork cutlets, and pork chops. A pork loin crown roast is arranged into a circle, either boneless or with rib bones protruding upward as points in a crown. Pork tenderloin, removed from the loin, should be practically free of fat.

-

Fatback – the subcutaneous fat and skin on the back are used to make pork rinds, a variety of cured "meats", lardons, and lard.

-

Side – although a fattier meat, it can be used for steaks or diced stir-fry meat. Side, or belly pork, may be rolled for roasting or cut for streaky bacon.

-

Legs – although any cut of pork can be cured, technically speaking only the back leg is entitled to be called a ham. Legs and shoulders, when used fresh, are usually cut bone-in for roasting, or leg steaks can be cut from the bone. Three common cuts of the leg include the rump (upper portion), centre, and shank (lower portion).

-

Hocks – both the front and hind, can be cooked and eaten, as can the knuckles and tail.

-

Spare ribs – are taken from the pig's ribs and the meat surrounding the bones. St. Louis-style spareribs have the sternum, cartilage, and skirt meat removed.

Culinary Uses:

Pork is eaten in several forms, including cooked (as roast pork). Pork can also be processed into different forms, which may also extend the shelf-life of the product, with the resultant products being cured (some hams, including the Italian prosciutto) or smoked or a combination of these methods (other hams, gammon, bacon or Pancetta).

Fried pieces of pork fat with a small amount of attached skin is known as crackling or pork rind is often eaten as a snack. Frying melts most of the fat from the pork rind. Uncooked pork rind may be cooked with beans or stewed vegetables or in soups.

The head of a pig can be used to make a preserved jelly called head cheese (brawn). Liver, chitterlings, blood (blood pudding or black pudding) and other offal from pigs are also widely used for food. It is also a common ingredient in sausages. Charcuterie is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as bacon, ham, sausage, terrines, galantines, pâtés, confit, rillettes, hocks (pig feet), and head cheese, primarily from pork.

In some religions, such as Judaism and Islam, there are religious restrictions on the consumption of pork.

Back to Menu  |

Beef Cattle

Cattle raised for human consumption are called "beef cattle". There are over 50 breeds of beef cattle. When raised in a feedlot cattle are known as feeder cattle. While the principal use of beef cattle is meat production, other uses include leather, and products used in shampoo and cosmetics.

Cattle raised for human consumption are called "beef cattle". There are over 50 breeds of beef cattle. When raised in a feedlot cattle are known as feeder cattle. While the principal use of beef cattle is meat production, other uses include leather, and products used in shampoo and cosmetics.

Beef can be harvested from cows, bulls (intact males), heifers (a heifer is a young cow before she has had her first calf), or steers (castrated males). Most young male offspring of dairy cows are sold for veal, and may be referred to as veal calves. It is one of the principal meats used in the cuisine of the Middle East, Australia, Argentina, Europe and the United States, and is also important in Africa, parts of East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Beef is considered a taboo food in some cultures, especially in Indian culture, and thence is eschewed by Hindus and Jains; it is also discouraged among some Buddhists.

In absolute numbers, the United States, Brazil, and the People's Republic of China are the world's three largest consumers of beef. On a per capita basis in 2009, Argentines ate the most beef at 64.6 kg per person; people in the US ate 40.2 kg, while those in the EU ate 16.9 kg. The world's largest exporters of beef are Brazil, Australia, and the United States.

Cattle raised for beef may be allowed to roam free on grasslands, or may be confined at some stage in pens as part of a large feeding operation called a feedlot (or concentrated animal feeding operation), where they are usually fed a ration of grain, protein, roughage and a vitamin/mineral preblend.

Beef from steers and heifers is equivalent, except for steers having slightly less fat and more muscle, all treatments being equal. A steer that weighs 1,000 lb (450 kg) when alive will make a carcase weighing about 615 lb (280 kg), once the blood, head, feet, skin, offal and guts have been removed. The carcase will then be hung in a cold room for between one and four weeks, during which time it loses some weight as water dries from the meat. When boned and cut by a butcher or packing house this carcase would then make about 430 lb (200 kg) of beef.

Depending on economics, the number of heifers kept for breeding varies. Older animals are used for beef when they are past their reproductive prime. The meat from older cows and bulls is usually tougher, so it is frequently used for ground beef (U.S.).

Cuts of Beef:

Beef is first divided into primal cuts: carcasses are split along the axis of symmetry into "halves", then across into forequarters and hindquarters. These are basic sections from which steaks and other subdivisions are cut. Since the animal's legs and neck muscles do the most work, they are the toughest; the meat becomes more tender as distance from hoof and horn increases.

Forequarter cuts:

-

Chuck – the source of bone-in chuck steaks and roasts (arm or blade), and boneless clod steaks and roasts, most commonly. The trimmings and some whole boneless chucks are ground for hamburgers.

-

Rib – contains part of the short ribs, rib eye steaks, prime rib, and standing rib roasts.

-

Brisket – used for barbecue, corned beef and pastrami.

-

Foreshank or shank – used primarily for stews and soups; it is not usually served any other way due to it being the toughest of the cuts.

-

Plate – the other source of short ribs, used for pot roasting, and the outside skirt steak, which is used for fajitas. The remainder is usually ground, as it is typically a cheap, tough, and fatty meat.

Hindquarter cuts:

-

The loin has two subprimals, or three if boneless:

-

Short loin – from which club, T-bone, and Porterhouse steaks are cut if bone-in, or strip steak (New York strip) and filet mignon if boneless,

-

Sirloin – less tender than short loin, but more flavorful; can be further divided into top sirloin and bottom sirloin (including tri-tip), and,

-

Tenderloin – the most tender. It can be removed as a separate subprimal, and cut into fillets, tournedos or tenderloin steaks or roasts, or can be left on wedge or flat-bone sirloin and T-bone and Porterhouse loin steaks.

-

-

Round – contains lean, moderately tough, lower fat (less marbling) cuts, which require moist cooking or lesser degrees of doneness. Some representative cuts are round steak, eye of round, top round and bottom round steaks and roasts.

-

Flank – used mostly for grinding, except for the long and flat flank steak, best known for use in London broil, and the inside skirt steak, also used for fajitas. Flank steaks are substantially tougher than the more desirable loin and rib steaks. Many recipes for flank steak use marinades or moist cooking methods, such as braising, to improve the tenderness and flavor.

Some cuts of beef are processed (corned beef or beef jerky), and trimmings, usually mixed with meat from older, leaner cattle, are ground, minced or used in sausages.

Culinary Uses:

The blood is used in some varieties of blood sausage. Other parts that are eaten include the oxtail, tongue, tripe from the reticulum or rumen, glands (particularly the pancreas and thymus, referred to as sweetbread), the heart, the brain (although forbidden where there is a danger of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, BSE), the liver, the kidneys, and the tender testicles of the bull (known in the US as calf fries, prairie oysters, or Rocky Mountain oysters). Some intestines are cooked and eaten as-is, but are more often cleaned and used as natural sausage casings. The lungs and the udder are classified as offals and considered to be unfit for human consumption in the US, however people in other countries use it as everyday food, or even in delicacies that command a high price. The bones are used for making beef stock.

Back to Menu  |

American Bison

American bison are now raised for meat and hides. The majority of bison in the world are being raised for human consumption. Bison meat is lower in fat and cholesterol than beef, a fact which has led to the development of beefalo, a fertile crossbreed of bison and domestic cattle. In 2005, about 35,000 bison were processed for meat in the U.S., with the National Bison Association and USDA providing a "Certified American Buffalo" program with birth-to-consumer tracking of bison via RFID ear tags. There is even a market for kosher bison meat; these bison are slaughtered at one of the few kosher mammal slaughterhouses in the U.S., and the meat is then distributed nationwide.

American bison are now raised for meat and hides. The majority of bison in the world are being raised for human consumption. Bison meat is lower in fat and cholesterol than beef, a fact which has led to the development of beefalo, a fertile crossbreed of bison and domestic cattle. In 2005, about 35,000 bison were processed for meat in the U.S., with the National Bison Association and USDA providing a "Certified American Buffalo" program with birth-to-consumer tracking of bison via RFID ear tags. There is even a market for kosher bison meat; these bison are slaughtered at one of the few kosher mammal slaughterhouses in the U.S., and the meat is then distributed nationwide.

There are approximately 500,000 bison in captive commercial populations (mostly plains bison) on about 4,000 privately owned ranches. The total population of bison calculated in conservation herds is approximately 30,000 individuals and the mature population consists of approximately 20,000 individuals. Of the total number presented, only 15,000 total individuals are considered wild bison in the natural range within North America (free-ranging, not confined primarily by fencing). Recent genetic studies of privately owned herds of bison show that many of them include animals with genes from domestic cattle. It is estimated that there are as few as 12,000 to 15,000 pure bison in the world.

Domestic Sheep

Lamb, mutton, and hogget are the meat of domestic sheep. The meat of a sheep in its first year is lamb; that of a juvenile sheep older than 1 year is hogget; and the meat of an adult sheep is mutton. The strict definitions for lamb, hogget and mutton vary considerably between countries. Under current United States federal regulations, only the term 'lamb' is used for ovine animals of any age, including ewes (female sheep) and rams (males).

The meat of a lamb is taken from the animal between one month and one year old, with a carcass weight of between 5.5 and 30 kilograms (12 and 65 lbs). This meat generally is more tender than that from older sheep and appears more often on tables in some Western countries. Hogget and mutton have a stronger flavor than lamb because they contain a higher concentration of species-characteristic fatty acids and are preferred by some. Mutton and hogget also tend to be tougher than lamb (because of connective tissue maturation) and are therefore better suited to casserole-style cooking, as in Lancashire hotpot, for example.

The meat of a lamb is taken from the animal between one month and one year old, with a carcass weight of between 5.5 and 30 kilograms (12 and 65 lbs). This meat generally is more tender than that from older sheep and appears more often on tables in some Western countries. Hogget and mutton have a stronger flavor than lamb because they contain a higher concentration of species-characteristic fatty acids and are preferred by some. Mutton and hogget also tend to be tougher than lamb (because of connective tissue maturation) and are therefore better suited to casserole-style cooking, as in Lancashire hotpot, for example.

Meat from sheep features prominently in several cuisines of the Mediterranean, for example in Greece; in North Africa and the Middle East; in the Basque culture, both in the Basque country of Europe and in the shepherding areas of the Western United States. In Northern Europe, mutton and lamb feature in many traditional dishes, including those of the North Atlantic islands and of the United Kingdom, particularly in the western and northern uplands, Scotland and Wales. It is also very popular in Australia. Lamb and mutton are very popular in Central Asia and South Asia, and in certain parts of China—where other red meats may be eschewed for religious or economic reasons—and in India, Iran and Pakistan. Barbecued mutton is also a specialty in some areas of the United States and Canada. However, meat from sheep is generally consumed far less in North America than in many European and Asian cuisines.

Lamb's liver, known as lamb's fry in Australia, is eaten in many countries and, along with the lungs and heart, is a major ingredient in the traditional Scottish dish of haggis. Lamb testicles, also known as lamb's fries (a term also used for other lamb offal), is another delicacy. Lamb's liver is the most common form of offal eaten in the UK, traditionally used in the family favorite (and pub grub staple) of liver with onions and/or bacon and mashed potatoes.

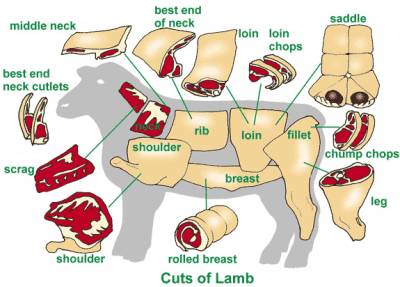

Cuts of Lamb:

Lamb is often sorted into three kinds of meat: forequarter, loin, and hindquarter.

Lamb is often sorted into three kinds of meat: forequarter, loin, and hindquarter.

The forequarter includes the neck, shoulder, front legs, and the ribs up to the shoulder blade. The hindquarter includes the rear legs and hip. The loin includes the ribs between the two.

Lamb chops are cut from the rib, loin, and shoulder areas. The rib chops include a rib bone; the loin chops include only a chine bone. Shoulder chops are usually considered inferior to loin chops; both kinds of chop are usually grilled. Breast of lamb (baby chops) can be cooked in an oven.

Leg of lamb is a whole leg. Saddle of lamb is the two loins with the hip. Leg and saddle are usually roasted, though the leg is sometimes boiled. Roasted leg and saddle may be served anywhere from rare to well-done.

Lamb shank is cut from the arm of shoulder, contains leg bone and part of round shoulder bone, and is covered by a thin layer of fat and fell (a thin, paperlike covering). A lamb shank can also be a cut of meat from the upper part of the leg.

Forequarter meat of sheep, as of other mammals, includes more connective tissue than some other cuts, and, if not from a young lamb, is best cooked slowly using either a moist method, such as braising or stewing, or by slow roasting or American barbecuing. Thin strips of fatty mutton can be cut into a substitute for bacon called macon.

Back to Menu  |

Domestic Goat

Goat meat is the meat of the domestic goat. It is often called chevon or mutton when the meat comes from adults, and cabrito or kid when from young animals. Market research in the United States suggests that "chevon eater" is more palatable to consumers than "goat eater". In the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean, and in some parts of Asia, particularly Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and India, the word “mutton” is often used colloquially to describe both goat and lamb meat, despite technically only referring to sheep meat.

Goat meat is the meat of the domestic goat. It is often called chevon or mutton when the meat comes from adults, and cabrito or kid when from young animals. Market research in the United States suggests that "chevon eater" is more palatable to consumers than "goat eater". In the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean, and in some parts of Asia, particularly Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and India, the word “mutton” is often used colloquially to describe both goat and lamb meat, despite technically only referring to sheep meat.

Goat has a reputation for strong, gamey flavor, but can be mild depending on how it is raised and prepared. Despite being classified as red meat, goat is leaner and contains less cholesterol and fat than both lamb and beef; therefore it requires low-heat, slow cooking to preserve tenderness and moisture.

In total consumption, goat is a distant fourth globally behind pork, beef, and chicken. However, the meat goat industry is the fastest growing segment of agriculture in the U.S. For the three major goat-producing states (AZ, NM, and TX) there were 1.2 million goats at the end of 2002. Today, the national total is closer 3.1 million goats.

The most common breeds of goat used in the U.S. goat meat industry are: San Clemente Island goat, Arapawa goat, Boer goat, Spanish goat, Kiko goat, Savanna goat, Myotonic goat, and the Pygmy goat. Except for San Clemente Island goats and Arapawa goats, the breeds of meat goats found in the United States today are of very recent origin. Development of the Boer and Savanna breeds began in South Africa about sixty years ago. These breeds are probably the oldest of the commonly used meat goat breeds found in the United States.

Goat is a staple of Africa, Asia and South/Central America, and a delicacy in a few European cuisines. The cuisines best known for their use of goat include Middle Eastern, North African, Indian, Pakistani, Mexican, and Caribbean. Goat has historically been less commonplace in American, Canadian and Northern European cuisines, but is finding a hold in some niche markets. While in the past goat meat in the West was confined to ethnic markets, it can now be found in a few upscale restaurants and grocers, especially in cities such as New York and San Francisco.

Culinary Uses:

Goat can be prepared in a variety of ways such as being stewed, curried, baked, grilled, barbecued, minced, canned, fried, or made into sausage. Goat jerky is also another popular variety. In Okinawa (Japan) goat meat is served raw in thin slices as yagisashi. In India, the rice-preparation of mutton biryani uses goat meat as a primary ingredient to produce a rich taste. Curry goat is a common traditional Indo-Caribbean dish. Cabrito, a specialty especially common in Latino cuisines such as Mexican, Peruvian, Brazilian, and Argentine, is usually slow roasted. Southern Italian and Greek cuisines are also both known for serving roast goat in celebration of Easter; goat dishes are also an Easter staple in the alpine regions of central Europe, often braised (Bavaria) or breaded and fried (Tyrol).

Back to Menu  |

Game Meat

Game is any animal hunted for food or not normally domesticated. Game animals are also hunted for sport. The type and range of animals hunted for food varies in different parts of the world. This will be influenced by climate, animal diversity, local taste and locally accepted view about what can or cannot be legitimately hunted.

Game is any animal hunted for food or not normally domesticated. Game animals are also hunted for sport. The type and range of animals hunted for food varies in different parts of the world. This will be influenced by climate, animal diversity, local taste and locally accepted view about what can or cannot be legitimately hunted.

In the U.S., Mexico and Canada, deer are the most commonly hunted big game. The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate North America lies in the Canadian Rocky Mountain and Columbia Mountain Regions between Alberta and British Columbia where all five North American deer species (White-tailed deer, Mule deer, Caribou, Elk, and Moose) can be found. They also live in the aspen parklands north of Calgary and Edmonton, where they share habitat with the moose. The adjacent Great Plains grassland habitats are left to herds of Elk, American Bison, and pronghorn antelope.

Other game species in North America include: Elk (wapiti), Groundhog, Moose, Opossum, Pronghorn, Rabbit, Raccoon, Squirrel, Wild boar (feral pig), and Common Snapping Turtle.

Venison:

Deer have long had economic significance to humans. Deer meat, for which they are hunted and farmed, is called venison.

Venison has enjoyed a rise in popularity in recent years, owing to the meat's lower fat content. It can often be obtained at less cost than beef by hunting, many families use it as a one to one substitute for beef, especially in the US mid-south, Midwest, Mississippi Valley and Appalachia. In many areas, this increased demand has led to a rise in the number of deer farms. What was once considered a meat for unsophisticated rural dwellers has become as exotic as ostrich meat to urbanites. Venison jerky can be purchased in some grocery stores, ordered online, and is served on some airlines.

Venison can be kosher, as deer are ruminants and possess completely split hooves, two of the requirements for land animals, and indeed is available kosher in places such as New York and Chicago.

Culinary Uses of Venison:

Venison may be eaten as steaks, tournedos, roasts, sausages, jerky and minced meat. It has a flavor reminiscent of beef, but is richer and can have a gamey note. Venison tends to have a finer texture and is leaner than comparable cuts of beef. However, like beef, leaner cuts can be tougher as well. Venison cooked beyond medium rare will take on a heavy gamey flavor.Venison lean is higher in moisture, similar in protein and lower in calories, cholesterol and fat than most cuts of grain-fed beef, pork, or lamb. Venison burgers are typically so lean as to require the addition of fat in the form of bacon, olive oil or cheese, or blending with beef, to achieve parity with hamburger cooking time, texture, and taste. Some deer breeders have expressed an interest in breeding for a fatter animal that displays more marbling in the meat.

Deer organ meat is called humble and is usually eaten as humble pie, a pastry filled with deer liver, heart and other offal.

Back to Menu  |

Organic vs. Conventional Factory-Farmed Meat

Conventional factory farm meat producers may seek to improve the fertility of female animals through the administration of gonadotrophic or ovulation-inducing hormones. Growth hormones, particularly anabolic agents such as steroids, are used to accelerate muscle growth in animals. In the midst of the mad cow disease crisis, this practice prompted the the European Union (EU), under pressure from its citizens, to ban the import of meat that contained artificial beef hormones, resulting in the beef hormone controversy—an international trade dispute.

One of the effects of the Beef Hormone Dispute in the US was to awaken the public's interest in the issue. In 1989, for example, the Consumer Federation of America and the Center for Science in the Public Interest both pressed for an adoption of a ban within the U.S. similar to that within the EU. In a study done in 2002, 85% of respondents wanted mandatory labeling on beef produced with growth hormones.

Sedatives may be administered to conventionally raised animals to counteract stress factors and increase weight gain. Many conventional meat producers feed their animals antibiotics on a daily basis. The feeding of antibiotics to certain animals has been shown to improve growth rates. Many of the antibiotics used are the same antibiotics humans rely on, and overuse of these drugs has already enabled bacteria to develop resistance to them, rendering them less effective in fighting infection. This practice is particularly prevalent in the USA, but has been banned in the EU, partly because it causes antibiotic resistance in pathogenic microorganisms.

Also, some herbicides and pesticide residues in the compound feed and premixes present a particular hazard due to their tendency to bioaccumulate in meat, potentially poisoning consumers. In the aftermath of the mad-cow disease crisis, while meat and bone meal (MBM) is no longer allowed in feed for ruminant animals, in some areas, including the U.S., MBM is still used to feed monogastric animals. All meat contains fat. Even if you trim off excess fat, fat resides intermingled in the muscle fiber although you may not be able to see it. In addition to publicized health issues related to fat intake, fat is where toxins are stored.

The residue of various hormones, steroids, antibiotics, sedatives, herbicides and pesticides in conventional factory-farmed meat is then consumed by humans. While some may argue that this doesn't pose an immediate or long-term health risk to adults, based on the results of several academic studies, the argument is less convincing for small children.

Conventional factory farmed animals are strictly fed a diet of fodder. Fodder or animal feed is any agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock such as cattle, goats, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. Most animal feed is from plants but some is of animal origin. "Fodder" refers particularly to food given to the animals, rather than that which they forage for themselve). It includes hay, straw, silage, compressed and pelleted feeds, oils and mixed rations, and also sprouted grains and legumes. Some agricultural by-products which are fed to animals may be considered unsavory by human consumers.

Compound feeds are feedstuffs that are blended from various raw materials and additives. These blends are formulated according to the specific requirements of the target animal. They are manufactured by feed compounders as meal type, pellets or crumbles. The main ingredients used in commercially prepared feed are the feed grains, which include corn, soybeans, sorghum, oats, and barley. The sale and manufacture of premixes is an industry within an industry.

Premixes are composed of microingredients such as vitamins, minerals, chemical preservatives, antibiotics, fermentation products, and other essential ingredients that are purchased from premix companies, usually in sacked form, for blending into commercial rations. Because of the availability of these products, a farmer who uses his own grain can formulate his own rations and be assured his animals are getting the recommended levels of minerals and vitamins.

Most conventional factory farmed animals are fed genetically modified foods. Genetically modified foods (or GM foods) are foods derived from genetically modified organisms. Genetically modified organisms have had specific changes introduced into their DNA by genetic engineering techniques. GM foods were first put on the market in the early 1990s. Typically, genetically modified foods are transgenic plant products: soybean, corn, canola, and cotton seed oil.

Organically grown animals are given 100% organic feed that has not been genetically modified nor contains MBM. The animals must have access to the outdoors and pastures to graze or forage. Organic meat producers use preventive measures—such as rotational grazing, a balanced diet and clean housing—to help minimize disease. Synthetic pesticides and fertilizers cannot be used on their land. Moreover, the animals must be raised without the use of antibiotics, growth hormones, steroids or other hormones, and cannot have their genes modified through genetic engineering. The farms are inspected and certified to make sure USDA regulations are in effect.

Back to Menu  |

"Natural Meat" and "Grass Fed"

According to the USDA these meats should be minimally processed. Minimal processing means that the product was processed in a manner that does not fundamentally alter the product. The meat should be free of preservatives, artificial ingredients and added color. But saline solution and some other preservatives are allowed. There is no specifics on how the animal is raised or the type of feed. The package label would have to list why the meat is considered natural and whether it was fed grains or grass or that there were no growth hormones or antibiotics.

Grass fed animals are allowed to graze on pastures which is more natural for them. How much depends on the individual farm's philosophy. Farmers rotate the pastures they graze on to protect the land. Some advertise 100% grass fed with no soy or corn feed and the meat has less saturated fat than grain fed meat. You would have to look at the label and website to see their particular feeding method.

The USDA has no specific definition for "free-range" beef, pork, and other non-poultry products. All USDA definitions of "free-range" refer specifically to poultry. No other criteria-such as the size of the range or the amount of space given to each animal-are required before beef, lamb, and pork can be called "free-range". Claims and labeling using "free range" are therefore unregulated. The USDA relies "upon producer testimonials to support the accuracy of these claims."

You may see "natural" and other terms such as "all natural," "free-range" or "hormone-free" on food labels. These descriptions must be truthful, but don't confuse them with the term "organic." Only foods that are grown and processed according to USDA organic standards can be labeled organic.

Slaughterhouse Process

Upon reaching a predetermined age or weight, livestock are usually transported en masse to the slaughterhouse. Depending on its length and circumstances, this may exert stress and injuries on the animals, and some may die en route. Unnecessary stress in transport may adversely affect the quality of the meat.

Meat is produced by killing the animal in question and cutting the desired flesh out of it. These procedures are called slaughter and butchery, respectively.

The slaughterhouse process differs by species and region and may be controlled by civil law as well as religious laws such as Kosher and Halal laws. Animals are usually slaughtered by being first stunned and then exsanguinated (bled out). In most forms of ritual slaughter, stunning is not allowed. Draining as much blood as possible from the carcass is necessary because blood causes the meat to have an unappealing appearance and is a very good breeding ground for microorganisms.

After exsanguination, the head, feet, hide (except hogs and some veal), excess fat, viscera and offal are removed, leaving only bones and edible muscle. Cattle and pig carcasses, but not those of sheep, are then split in half along the mid ventral axis, and the carcass is cut into wholesale pieces.

There has been criticism of the methods of preparation, herding, and killing within some slaughterhouses, and in particular of the speed with which the slaughter is sometimes conducted. Investigations by animal welfare and animal rights groups have indicated that a proportion of these animals are being skinned or gutted while apparently still alive and conscious. Many, but not all, of these supposed cases are miss-interpretations post-mortum death twitching as shown by researchers.

There has also been criticism of the methods of transport of the animals, who are driven for hundreds of miles to slaughterhouses in conditions that often result in crush injuries and death en route.

Over the last few decades, some research has been done toward making slaughterhouses more humane; one well-known scientist in this field is Temple Grandin. While Grandin's primary objective is to help slaughterhouse operators improve efficiency and profit, she suggested that reducing the stress and suffering of animals being led to slaughter may help achieve this aim.

Under hygienic conditions and without other treatment, meat can be stored at above its freezing point (-1.5 °C) for about six weeks without spoilage, during which time it undergoes an aging process that increases its tenderness and flavor. As the muscle pigment myoglobin denatures, its iron oxidates, which may cause a brown discoloration near the surface of the meat.

Back to Menu  |

Poultry

Poultry is a category of domesticated birds kept by humans for the purpose of collecting their eggs, or killing for their meat and/or feathers. These most typically include fowl, especially chickens, quails and turkeys and "waterfowl" (e.g. domestic ducks and domestic geese). Poultry also includes other birds which are killed for their meat, such as pigeons, doves, Emu, Ostrich and Rhea, or birds considered to be game, like pheasants.

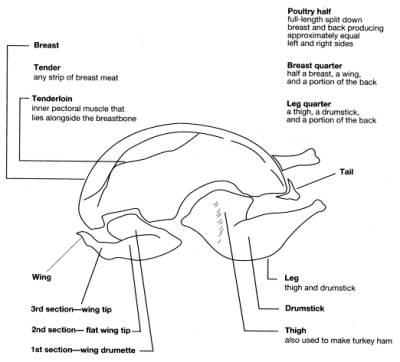

The meatiest parts of a bird are the flight muscles on its chest, called breast meat, and the walking muscles on the first and second segments of its legs, called the thigh and drumstick, respectively.

White Meat and Dark Meat

Dark meat, which avian myologists (bird muscle scientists) refer to as "red muscle," is used for sustained activity—chiefly walking, in the case of a chicken. The dark color comes from the protein myoglobin, which plays a key role in oxygen uptake within cells. White meat or "white muscle", in contrast, is suitable only for short, ineffectual bursts of activity such as, for chickens, flying. Thus the chicken's leg and thigh meat are dark while its breast meat (which makes up the primary flight muscles) is white. Other birds with breast muscle more suitable for sustained flight, such as ducks and geese, have red muscle (and therefore dark meat) throughout.

Nutritional Content

Once a meat consumed only occasionally, the common availability and lower cost has made chicken a common meat product within developed nations. Growing concerns over the cholesterol content of red meat in the 1980s and 1990s further resulted in increased consumption of chicken.

All muscle tissue is very high in protein, containing all of the essential amino acids, and in most cases is a good source of zinc, vitamin B12, selenium, phosphorus, niacin, vitamin B6, choline, riboflavin and iron. Muscle tissue is very low in carbohydrates and does not contain dietary fiber. The fat content of meat can vary widely depending on the species and breed of animal, the way in which the animal was raised, including what it was fed, the anatomical part of the body.

Most poultry meats contain a full complement of the amino acids required for the human diet. Fruits and vegetables, by contrast, are usually lacking several essential amino acids contained in meat. It is for this reason that people who abstain from eating all meat need to plan their diet carefully to include sources of all the necessary amino acids.

The white meat is generally considered healthier than dark meat because of its lower fat content, but the nutritional differences are small. Furthermore, chicken and turkey generally have low fat in their meat itself, however it is highly concentrated on their skin, which should be avoided when low intake of fat is necessary.

Health Concerns

-

Consumption of large quantities of meat, like overconsumption of any caloric food, has certain adverse effects which can include: obesity, heart disease, and constipation. In recent years, health concerns have been raised about the consumption of meat increasing the risk of cancer. Bird and animal fat, particularly from ruminants, tends to have a higher percentage of saturated fat vs. monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat when compared to vegetable fats, with the exception of some tropical plant fats; consumption of which has been correlated with various health problems. The saturated fat found in meat has been associated with significantly raised risks of colon cancer. USDA claims (see Dietary Guidelines for Americans) that consumption of meat as a source of protein in the human diet is crucial have been resoundingly contradicted by recent studies.

-

The correlation of meat, including poultry, consumption to increased risk of heart disease is controversial. A recent study in 2010 involving over one million people who ate meat found that only processed meat had an adverse risk in relation to coronary heart disease. The study suggests that eating 50g (less than 2oz) of processed meat per day increases risk of coronary heart disease by 42%, and diabetes by 19%. Chicken meat contains about two to three times as much polyunsaturated fat than most types of red meat when measured as weight percentage. Chicken generally includes low fat in the meat itself, however it is highly concentrated on its skin, which should be avoided when low intake of fat is necessary.

-

Antibiotics have been used on poultry in large quantities since the 1940s, when it was found that the adjustment of intestinal flora, favoring "good" bacteria while suppressing "bad" bacteria resulted in poultry that grew bigger faster. Because the antibiotics used are not absorbed by the gut, they do not put antibiotics into the meat or eggs. To prevent any residues of antibiotics in chicken meat, any given antibiotics are required to have a "withdrawal" period before they can be slaughtered. Samples of poultry at slaughter are randomly tested by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), and shows a very low percentage of residue violations.

-

Unlike with beef production, hormone use in poultry production is illegal in the United States.

-

The spoilage of meat occurs, if untreated, in a matter of hours or days and results in the meat becoming unappetizing, poisonous or infectious. Spoilage is caused by the practically unavoidable infection and subsequent decomposition of meat by bacteria and fungi, which are borne by the animal itself, by the people handling the meat, and by their implements; the latter two are the most common scenario.

The bacteria most commonly infecting meat while it is being processed, cut, packaged, transported, sold and handled include Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli, B. proteus, Staph. epidermidis and Staph.aureus, Clostridium welchii, B. cereus and faecal streptococci. These bacteria are all commonly carried by humans; infectious bacteria from the soil include Clostridium botulinum. Among the molds/fungi commonly infecting meat are Penicillium, Mucor, Cladosporium, Alternaria, Sporotrichium and Thamnidium. As these microorganisms colonize a piece of meat, they begin to break it down, leaving behind toxins that can cause enteritis or food poisoning, potentially lethal in the rare case of botulism. The microorganisms do not survive a thorough cooking of the meat, but several of their toxins and microbial spores do. The microbes may also infect the person eating the meat, although the microflora of the human gut is normally an effective barrier against this. -

A recent study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute showed that nearly half (47%) percent of the meat and poultry in U.S. grocery stores were contaminated with Staph. aureus, with more than half (52%) of those bacteria resistant to antibiotics.

-

According to Consumer Reports, "1.1 million or more Americans [are] sickened each year by undercooked, tainted chicken." A USDA study discovered E. coli in 99% of supermarket chicken, the result of chicken butchering not being a sterile process. However, the same study also cautions that the type of E. coli turned up was in every case a non-lethal form distinct from the more dangerous "O157:H7" strain. Many of these chickens, furthermore, had relatively low levels of contamination. E. coli can be killed by proper cooking times, but there is still some risk associated with it, and its near-ubiquity in commercially farmed chicken is troubling to some.

Back to Menu  |

Chicken

Because of its relatively low cost, chicken is one of the most used meats in the world. Nearly all parts of the bird can be used for food, and the meat can be cooked in many different ways.

Because of its relatively low cost, chicken is one of the most used meats in the world. Nearly all parts of the bird can be used for food, and the meat can be cooked in many different ways.

Typically, the muscle tissue (breast, legs, thigh, etc.), liver, heart, and gizzard are processed for food. Chicken feet are commonly eaten, especially in Caribbean and Chinese cuisine. Chicken wings refers to a serving of the wing sections of a chicken.

Exotic parts like pygostyle (chicken's buttocks) and testicles are commonly eaten in East Asia and some parts of South East Asia.

Whole Chickens:

Whole chickens are marketed in the United States as fryers, broilers, and roasters.

-

Fryers are the smallest size (2.5-4 lbs dressed for sale), and the most common, as chicken reach this size quickly (about 7 weeks). Most dismembered packaged chicken would be sold whole as fryers.

-

Broilers are larger than fryers. They are typically sold whole.

-

Roasters, or roasting hens, are the largest chickens commonly sold (3-5 months and 6-8 lbs) and are typically more expensive.

-

Even larger and older chickens are called stewing chickens but these are no longer usually found commercially.

The names reflect the most appropriate cooking method for the surface area to volume ratio. For a fast method of cooking, such as frying, a small bird is appropriate: frying a large piece of chicken results in the inside being undercooked when the outside is ready.

Chicken is also sold in dismembered pieces.

-

Pieces may include quarters, or fourths of the chicken. A chicken is typically cut into two leg quarters and two breast quarters. Each quarter contains two of the commonly available pieces of chicken.

-

A leg quarter contains the thigh, drumstick and a portion of the back; a leg has the back portion removed.

-

A breast quarter contains the breast, wing and portion of the back; a breast has the back portion and wing removed.

Pieces may be sold in packages of all of the same pieces, or in combination packages.

-

Whole chicken cut up refers to either the entire bird cut into 8 individual pieces (8-piece cut); or sometimes without the back.

-

Pick of the Chicken, or similar titles, refers to a package with only some of the chicken pieces. Typically the breasts, thighs, and legs without wings or back. Thighs and breasts are sold boneless and/or skinless.

-

Dark meat (legs, drumsticks and thighs) pieces are typically cheaper than white meat pieces (breast, wings).

-

Chicken livers and/or gizzards are commonly available packaged separately.

-

Other parts of the chicken, such as the neck, feet, combs, etc. are not widely available except in countries where they are in demand, or in cities that cater to ethnic groups who favor these parts.

Freezing:

Raw chicken can be frozen for up to two years without significant changes in flavor or texture. For optimal quality, however, a maximal storage time in the freezer of 12 months is recommended for uncooked whole chicken, 9 months for uncooked chicken parts, 3 to 4 months for uncooked chicken giblets, and 4 months for cooked chicken.

It is safe to freeze chicken directly in its original packaging, however this type of wrap is permeable to air and quality may diminish over time. Therefore, for prolonged storage, it is recommended to overwrap these packages. If previously frozen chicken is purchased at a retail store, it can be refrozen if it has been handled properly. Chicken can be cooked or reheated from the frozen state, but it will take approximately one and a half times as long to cook.

Culinary Uses:

Chicken is typically eaten cooked as when raw it often contains salmonella. Raw or rare chicken dishes appear in Ethiopian cuisine and Japanese cuisine. Chicken can be cooked in many ways. It can be made into sausages, skewered, put in salads, grilled, breaded and deep-fried, or used in various curries. There is significant variation in cooking methods amongst cultures.

Historically common methods include roasting, baking, broasting, and frying. Today, chickens are frequently cooked by deep frying and prepared as fast foods such as fried chicken, chicken nuggets, chicken lollipops or buffalo wings. They are also often grilled for salads or tacos. Other popular chicken dishes include chicken soup, tandoori chicken, butter chicken, and chicken rice.

Chicken bones are hazardous to health as they tend to break into sharp splinters when eaten, but they can be simmered with vegetables and herbs for hours or even days to make chicken stock.

Back to Menu  |

Domestic Turkey

The modern domesticated turkey descends from the wild turkey. Industrialized farming has made it very cheap for the amount of meat it produces. Turkeys are traditionally eaten as the main course of Christmas feasts in much of the world (stuffed turkey) since appearing in England in the 16th century, as well as for Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada, though this tradition has its origins in modern times, rather than colonial as is often supposed. While eating turkey was once mainly restricted to special occasions such as these, turkey is now eaten year-round and forms a regular part of many diets.

The modern domesticated turkey descends from the wild turkey. Industrialized farming has made it very cheap for the amount of meat it produces. Turkeys are traditionally eaten as the main course of Christmas feasts in much of the world (stuffed turkey) since appearing in England in the 16th century, as well as for Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada, though this tradition has its origins in modern times, rather than colonial as is often supposed. While eating turkey was once mainly restricted to special occasions such as these, turkey is now eaten year-round and forms a regular part of many diets.

There are currently eight breeds of domestic turkeys recognized by the American Poultry Association, but many more exist as officially unrecognized variants or as recognized breeds in other countries. The Broad-breasted White is the commercial turkey of choice for large scale industrial turkey farms, and consequently is the most consumed variety of the bird. Usually the turkey to receive a "presidential pardon", a US custom, is a Broad breasted White. The Broad-breasted Bronze is another commercially developed strain of table bird. The Narragansett Turkey is a popular heritage breed named after Narraganset Bay in New England.

Sold As:

Turkeys are sold sliced and ground, as well as "whole" in a manner similar to chicken with the head, feet, and feathers removed. A large amount of turkey meat is also sold processed.

-

Frozen whole turkeys remain popular.

-

Sliced turkey is frequently used as a sandwich meat or served as cold cuts; in some cases where recipes call for chicken it can be used as a substitute.

-

Ground turkey is sold just as ground beef, and is frequently marketed as a healthy beef substitute.

-

It can be smoked and as such is sometimes sold as turkey ham.

Cooking:

Without careful preparation, cooked turkey is usually considered to end up less moist than other poultry meats such as chicken or duck. Turkeys are usually baked or roasted in an oven for several hours, often while the cook prepares the remainder of the meal. Sometimes, a turkey is brined before roasting to enhance flavor and moisture content. This is necessary because the dark meat requires a higher temperature to denature all of the myoglobin pigment than the white meat (very low in myoglobin), so that fully cooking the dark meat tends to dry out the breast. Brining makes it possible to fully cook the dark meat without drying the breast meat. Turkeys are sometimes decorated with turkey frills prior to serving.

In some areas, particularly the American South, they may also be deep fried in hot oil (often peanut oil) for 30 to 45 minutes by using a turkey fryer. Deep frying turkey has become something of a fad, with hazardous consequences for those unprepared to safely handle the large quantities of hot oil required.

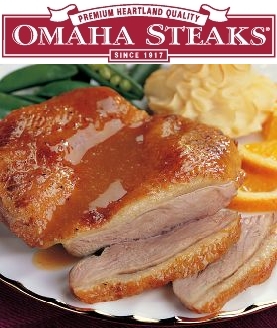

Domestic Duck

Domestic ducks have been farmed for thousands of years, possibly starting in Southeast Asia. Ducks are farmed for their meat, eggs, and down. A minority of ducks are also kept for foie gras production.

Domestic ducks have been farmed for thousands of years, possibly starting in Southeast Asia. Ducks are farmed for their meat, eggs, and down. A minority of ducks are also kept for foie gras production.

They are not as popular as the chicken, because chickens have much more white lean meat and are easier to keep confined, making the total price much lower for chicken meat, whereas duck is comparatively expensive and, while popular in the haute cuisine, appears less frequently in mass market food industry and restaurants in the lower price range.

The most common duck meat consumed in the United States is the Peking duck. Because most commercially raised Pekins come from Long Island, New York, Pekins are also sometimes called "Long Island" ducks, despite being of Chinese origin. Some specialty breeds have become more popular in recent years, notably the Muscovy duck, and the Moulard duck.

Duck meat is derived primarily from the breasts and legs of ducks. The meat of the legs is darker and somewhat fattier than the meat of the breasts, although the breast meat is darker than the breast meat of a chicken or a turkey. Being waterfowl, ducks have a layer of heat-insulating subcutaneous fat between the skin and the meat.

Culinary Uses:

Duck is used in a variety of dishes around the world, most of which involve roasting for at least part of the cooking process to aid in crisping the skin.

De-boned duck breast can be grilled like steak, usually leaving the skin and fat on. Magret refers specifically to the breast of a mallard (wild duck) or Barbary (Muscovy) duck that has been force-fed to produce foie gras, a popular and well-known delicacy in French cuisine. Their breasts are large and have a much thinner layer of fat than do the Peking or Long Island duckling. Internal organs such as heart and kidneys may also be eaten; the liver in particular is often used as a substitute for goose liver in foie gras.

Domestic Geese:

Domestic geese are domesticated Grey geese (either Greylag geese or Swan geese) kept as poultry for their meat, eggs, and down feathers since ancient times. Geese produce large edible eggs, weighing 120-170 g. They can be used in cooking just like chicken's eggs, though they have proportionally more yolk, and this cooks to a slightly denser consistency. The taste is much the same as that of a chicken egg.

Domestic geese are domesticated Grey geese (either Greylag geese or Swan geese) kept as poultry for their meat, eggs, and down feathers since ancient times. Geese produce large edible eggs, weighing 120-170 g. They can be used in cooking just like chicken's eggs, though they have proportionally more yolk, and this cooks to a slightly denser consistency. The taste is much the same as that of a chicken egg.

There are currently eleven breeds of domestic geese recognized by the American Poultry Association, but many more exist as officially unrecognized variants or as recognized breeds in other countries: American Buff, Pilgrim, Canada, Toulouse, Embden, African, Pomeranian, Chinese, Sebastopol, and Egyptian Goose. The Toulouse is the breed most used for the production of foie gras.

Roast Goose:

Roast goose is a dish found within Chinese and European cuisine. Within the Cantonese cuisine, it is made by roasting geese with seasoning in a charcoal furnace at high temperature. Roasted geese of high quality have crisp skin with juicy and tender meat. Slices of roasted goose are generally served with plum sauce. English & German-speaking people roasted geese traditionally only on appointed holidays. Roasted goose is a favored Christmas dish as well as commonly eaten on St. Martin's Day. The most prevalent stuffings are apples, sweet chestnuts, prunes and onions. Typical seasonings include salt and pepper, mugwort, or marjoram. Also used are red cabbage, Knödel, and gravy, which are used to garnish the goose. Another version of roast goose is the Alsatian-style with Bratwurst-stuffing and sauerkraut as garnish.

Foie Gras:

Foie gras is a food product made of the liver of a duck or goose that has been specially fattened. This fattening is typically achieved through gavage (force-feeding) corn, according to French law, though outside of France it is occasionally produced using natural feeding. Foie gras is a popular and well-known delicacy in French cuisine. Its flavor is described as rich, buttery, and delicate, unlike that of a regular duck or goose liver. Foie gras is sold whole, or is prepared into mousse, parfait, or pâté (the lowest quality), and may also be served as an accompaniment to another food item, such as steak.

Gavage-based foie gras production is controversial, due to the force feeding procedure. In modern gavage-based foie gras production, force feeding takes place 12–18 days before slaughter. The duck or goose is typically fed a controlled amount of corn mash through a tube inserted in the animal's esophagus. Foie gras production has been banned in some members of the European Union, Turkey, Israel and the state of California because of the force-feeding process. Most foie gras producers do not consider their methods cruel, insisting that it is a natural process exploiting the animals' natural features. Producers argue that wild ducks and geese naturally ingest large amounts of whole food and gain weight before migration. Foie gras producers also contend that geese and ducks do not have a gag reflex, and therefore do not find force feeding uncomfortable.

Squab (Domestic Pigeon)

In culinary terminology, squab is a young domestic pigeon or its meat. In parts of the developed world, squab meat is thought of as exotic or distasteful because the feral pigeon is considered an unsanitary urban pest. However, squab meat is regarded as safer than some other poultry products as it harbors fewer pathogens, and may be served between medium and well done.

In culinary terminology, squab is a young domestic pigeon or its meat. In parts of the developed world, squab meat is thought of as exotic or distasteful because the feral pigeon is considered an unsanitary urban pest. However, squab meat is regarded as safer than some other poultry products as it harbors fewer pathogens, and may be served between medium and well done.

The practice of domesticating pigeon as livestock may have come from the Middle East; historically, squabs or pigeons have been consumed in many civilizations throughout much of recorded history, including Ancient Egypt, Rome and Medieval Europe. Today, squab is eaten in many countries, including France, the United States, Italy, the Maghreb, and several Asian countries.

Squabs are raised to the age of roughly a month before being killed for eating; they have reached adult size but have not yet flown. The modern squab industry uses utility pigeons which have been artificially selected for weight gain, quick growth, health when kept in large numbers, and health of their infants. Industrially raised pigeons have young which weigh 1.3 pounds (0.59 kg) when of age, as opposed to traditionally raised pigeons, which weigh 0.5 pounds (0.23 kg).

Squab is dark meat, and the skin is fatty, like that of duck. The meat is very lean, easily digestible, and "is rich in proteins, minerals, and vitamins". Squab has been described as having a "silky" texture, as it is very tender and fine-grained. The meat is widely described as tasting like dark chicken meat, and has a mild berry flavor.

Culinary Uses:

In the United States of America, squab is "increasingly a specialty item", as the larger and cheaper chicken displaced it. However, squab produced from specially-raised utility pigeons continues to be a part of the menus at American haute cuisine restaurants and has enjoyed endorsements from some celebrity chefs. Accordingly, squab is often sold for much higher prices than other poultry, sometimes as high as $8 U.S. per pound. In Chinese cuisine, squab is a part of celebratory banquets for holidays such as Chinese New Year, usually served deep-fried. The greatest volume of U.S. squab is currently sold within Chinatowns.

Squab's flavor lends itself to complex red or white wines. Usually considered a delicacy, squab is tender, moist and richer in taste than many commonly-consumed poultry meats, but there is relatively little meat per bird, the meat being concentrated in the breast. Typical dishes include breast of squab (sometimes as the French salmis), Egyptian mahshi (stuffed with rice and herbs), and the Moroccan dish pastilla. In Spain and France, squab is also preserved as a confit.

Commercially raised birds "take only half as long to cook" as traditionally raised birds, and are suitable for roasting, grilling, or searing, whereas the traditionally raised birds are better suited to casseroles and slow-cooked stews. The meat from older and wild pigeons is tougher than squab, and requires a long period of stewing or roasting to tenderize.

Domestic Quail

The Common Quail was previously much favored in French cooking, but quail for the table are now more likely to be domesticated Japanese Quail. The Common Quail is also part of Maltese cuisine and Portuguese cuisine, as well as in Indian cuisine such as a bhuna and Kerala Specialties.

The Common Quail was previously much favored in French cooking, but quail for the table are now more likely to be domesticated Japanese Quail. The Common Quail is also part of Maltese cuisine and Portuguese cuisine, as well as in Indian cuisine such as a bhuna and Kerala Specialties.

Quails are commonly eaten complete with the bones, since these are easily chewed and the small size of the bird makes it inconvenient to remove them.

Quail that have fed on hemlock (e.g. during migration) may induce acute renal failure due to accumulation of toxic substances from the hemlock in the meat; this problem is referred to as "coturnism". Therefore it is safer to buy commerically farmed quail. As with most commercial poultry farming, using genetic selection and special feed, these will be fast-growing, heavy, and large-breasted birds compared to their wild counterparts. They will normally cater to retail grocers, health food stores, gourmet restaurants, and in some cases directly to the consumer.

Poultry Farming

Poultry farming is the practice of raising domesticated birds such as chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese, as a subcategory of animal husbandry, for the purpose of farming meat or eggs for food.

More than 50 billion chickens are reared annually as a source of food, for both their meat and their eggs. Chickens farmed for meat are called broilers, whilst those farmed for eggs are called egg-laying hens. Some hens can produce over 300 eggs a year. Chickens will naturally live for 6 or more years. After 12 months, the hen’s productivity will start to decline. This is when most commercial laying hens are slaughtered for their meat.

The majority of poultry are raised on factory farms using intensive farming techniques. According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74% of the world's poultry meat, and 68% of eggs are produced this way. One alternative to intensive poultry farming is free range farming.

Friction between these two main methods has led to long term issues of ethical consumerism. Opponents of intensive farming argue that it harms the environment and creates health risks, as well as abusing the animals themselves. Advocates of intensive farming say that their highly efficient systems save land and food resources due to increased productivity, stating that the animals are looked after in state- of-the-art environmentally controlled facilities. A few countries have banned cage-system housing, including Sweden and Switzerland.

Other alternatives to conventional intensive farming techniques include pastured poultry and organically raised poultry.

Some groups which advocate for more humane treatment of chickens claim that chickens are intelligent. Dr. Chris Evans of Macquarie University claims that their range of 20 calls, problem solving skills, use of representational signaling, and the ability to recognize each other by facial features demonstrate the intelligence of chickens.

Factory Farmed Poultry

Poultry raised on factory farms strictly remain confined indoors at high-stocking density throughout their short life. Factory farms routinely use a number of intensive farming techniques in raising poultry.

Poultry raised on factory farms strictly remain confined indoors at high-stocking density throughout their short life. Factory farms routinely use a number of intensive farming techniques in raising poultry.

Since their cages do not permit birds to roam, the closeness of chickens to one another frequently causes cannibalism. In close confinement, cannibalism and aggression is common among turkeys, ducks, pheasants, quail, and egg-laying strains of chickens of many breeds. The tendency to cannibalism varies among different strains of chickens, but does not manifest itself consistently. Some flocks of the same breed may be entirely free from cannibalism, while others, under the same management, may have a serious outbreak.

De-beaking (removing a portion of the bird's beak with a hot blade so the bird cannot effectively peck) is common in egg-laying strains of chickens and turkeys as a preventive measure to reduce the incidence of cannibalism and feather pecking and improve livability. However, de-beaking does not address the fact that cannibalistic tendencies stem from stress hormone elevation, which results directly from overcrowding conditions, and that these stress hormones inhibit the conditions necessary for the development of omega-3 fatty acids and drastically diminish the nutritive value of both the meat and eggs. As a result of that, the addition of omegas to chicken feed has been an attempt to address the inability of chickens to have enough access to insects and seeds during daily forage. A rule of thumb is that if de-beaking is required to address chickens' excessive pecking and cannibalism behavior, the chickens are under stress and the meat and egg products, as a result, are of of lesser quality.

On chicken farms using intensive farming techniques, meat chickens, commonly called broilers, are floor-raised on litter such as wood shavings or rice hulls, indoors in climate-controlled housing. Poultry producers routinely use nationally approved medications, such as antibiotics, in feed or drinking water, to treat disease or to prevent disease outbreaks arising from overcrowded or unsanitary conditions. In the U.S., the national organization overseeing chicken production is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Some FDA-approved medications are also approved for improved feed utilization.

Under intensive farming methods, a broiler chicken will live less than six weeks before slaughter. This is half the time it would take traditionally. This compares with free-range chickens which will usually be slaughtered at 8 weeks, and organic ones at around 12 weeks.

In intensive broiler sheds, the air can become highly polluted with ammonia from the droppings. This can damage the chickens’ eyes and respiratory systems and can cause painful burns on their legs (called hock burns) and feet. Chickens bred for fast growth have a high rate of leg deformities because they cannot support their increased body weight. Because they cannot move easily, the chickens are not able to avoid heat, cold or dirt as they would in natural conditions. The added weight and overcrowding also puts a strain on their hearts and lungs.

Back to Menu  |

Free-range Poultry

In some cases, the chickens are given continuous access to an outdoor range during the daytime and sheds where they are housed at night, enabling the poultry to move around, forage for their natural diet and live in cleaner conditions than those in batteries. Unlike battery farms, free range farmers have little control over the food their animals come across which can lead to unreliable productivity. Because they grow slower and have opportunities for exercise free-range chickens have better leg and heart health and a much higher quality of life. They live at least 56 days. In some farms, the manure from free range poultry can be used to benefit crops.

In some cases, the chickens are given continuous access to an outdoor range during the daytime and sheds where they are housed at night, enabling the poultry to move around, forage for their natural diet and live in cleaner conditions than those in batteries. Unlike battery farms, free range farmers have little control over the food their animals come across which can lead to unreliable productivity. Because they grow slower and have opportunities for exercise free-range chickens have better leg and heart health and a much higher quality of life. They live at least 56 days. In some farms, the manure from free range poultry can be used to benefit crops.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) requires that chickens raised for their meat have access to the outside in order to receive the free-range certification. However, the USDA regulations do not specify the quality or size of the outside range nor the duration of time an animal must have access to the outside. There is no requirement for access to pasture, and there may be access to only dirt or gravel. Claims and labeling using "free range" are therefore unregulated. The USDA relies "upon producer testimonials to support the accuracy of these claims."

Instead, the term "free range" is mainly used as a marketing term rather than a husbandry term, meaning something on the order of, "low stocking density" "pasture-raised", "grass-fed", "old-fashioned", "humanely raised", etc. In poultry-keeping, "free range" is widely confused with yarding, which means keeping poultry in fenced yards.

Alternative terminology can also be used to make high-density confinement sound more palatable. For example: "cage-free", "free-running", " free-roaming", "naturally nested", etc. are used as an alternative to the technical term "high-density floor confinement". Whether high-density floor confinement is more humane than high-density cage confinement is arguable, but in any event, high-density confinement (of whatever type) is the antithesis of free range.

The broadness of "free range" in the U.S. has caused some people to look for alternative terms. "Pastured poultry" is a term promoted by farmer/author Joel Salatin for broiler chickens raised on grass pasture for all of their lives except for the initial brooding period. The Pastured Poultry concept is promoted by the American Pastured Poultry Producers' Association (APPPA), an organization of farmers raising their poultry using Salatin's principles.

Back to Menu  |